Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

“We decide whether the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) authorizes the President to impose tariffs.”

That is the first sentence of Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion for the court in Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump, decided today, Feb. 20, 2026. The case arose from a challenge to broad tariffs that the executive branch imposed pursuant to IEEPA’s grant of authority to “regulate . . . importation.” The court’s decision on whether the president had the power to do so was unambiguous:

The President asserts the extraordinary power to unilaterally impose tariffs of unlimited amount, duration, and scope. In light of the breadth, history, and constitutional context of that asserted authority, he must identify clear congressional authorization to exercise it. IEEPA’s grant of authority to “regulate . . . importation” falls short. IEEPA contains no reference to tariffs or duties. The Government points to no statute in which Congress used the word “regulate” to authorize taxation. And until now no President has read IEEPA to confer such power. We claim no special competence in matters of economics or foreign affairs. We claim only, as we must, the limited role assigned to us by Article III of the Constitution. Fulfilling that role, we hold that IEEPA does not authorize the President to impose tariffs.

The decision also resolved the companion case, Trump v. V.O.S. Selections, by affirming the lower court judgment in that case, and vacated and remanded the district court judgment in Learning Resources itself for dismissal on jurisdictional grounds. The merits holding, however, is unqualified: IEEPA is not a tariff statute.

The court’s coalition

Roberts announced the judgment and wrote the principal opinion, but that opinion carries two distinct coalitions:

Parts I, II-A-1, and II-B constitute the opinion of the court, joined by Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, Barrett, and Jackson – a six-justice coalition. These sections focus on the statute: reading the text, examining the constitutional backdrop, and concluding that IEEPA does not authorize tariffs.

Parts II-A-2 and III, which contains discussion of the major questions doctrine, or the idea that “clear congressional authorization” is necessary to authorize presidential actions regarding significant issues, were joined only by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett – making those portions a three-justice plurality, not a majority holding.

Beyond Roberts, six separate writings were filed:

- Gorsuch concurred

- Barrett concurred

- Kagan concurred in part and in the judgment, joined by Sotomayor and Jackson

- Jackson concurred in part and in the judgment

- Thomas dissented separately

- Kavanaugh dissented, joined by Thomas and Alito

What each opinion said and how they compare

The Roberts opinion of the court – six justices

The six-justice opinion analyzes the statute. This reads “regulate . . . importation” against its textual neighbors and statutory context, observes that IEEPA contains no reference to tariffs or duties, and notes that the government could not identify a single statute in which Congress used “regulate” to authorize taxation. The opinion draws on the 1824 case of Gibbons v. Ogden for the proposition that tariffs are “a branch of the taxing power,” and concludes that if “regulate . . . exportation” included taxation, IEEPA would authorize what Article I provides to Congress, not the president.

The Roberts plurality – major questions – three justices

As noted above, the narrower Roberts-Gorsuch-Barrett plurality (Parts II-A-2 and III) applies the major questions doctrine. This requires “clear congressional authorization” for the claimed power, holds there is no emergency exception to that requirement here, holds that foreign-affairs implications do not displace the doctrine, and treats as “telling” that in IEEPA’s fifty-year existence no president had invoked it to impose tariffs.

The concurrences

Gorsuch (46 pages) joined Roberts in full and wrote the second-longest opinion to defend the major questions framework and write on the non-delegation doctrine (the principle that Congress cannot grant legislative powers to other branches)

Barrett (4 pages) joined Roberts in full and wrote briefly to challenge Gorsuch’s framing of the major questions doctrine

Kagan (7 pages, joined by Sotomayor and Jackson) joined the six-justice portions but not the major questions plurality. Her core position is stated explicitly: ordinary tools of statutory interpretation are sufficient – meaning she does not need the major questions “thumb on the scale” to reach the same result.

Jackson (5 pages) joined the same portions as Kagan and writes separately to rely on the legislative record – House and Senate Reports – to anchor the congressional intent when IEEPA was enacted. This is the opinion’s primary legislative-history-positive writing, and it stands in direct methodological tension with Gorsuch’s explicit caution against those same materials.

The dissents

Thomas (18 pages) dissented separately to describe historical practice, which in his view supports the president’s ability to levy tariffs under IEEPA

Kavanaugh (63 pages, joined by Thomas and Alito) is the longest opinion in the case and the most comprehensive defense of the government’s position. His dissent:

- Structures the case as the president acting pursuant to congressional authorization

- Argues “regulate . . . importation” and “adjust . . . imports” are not meaningfully distinguishable

- Contends the Nixon-era Trading with the Enemy Act tariff episode (the predecessor to IEEPA) means the claimed authority was not “unheralded”

- Argues the major questions doctrine has never been applied to a foreign affairs statute and should not be applied here

- Warns that applying the majority’s new approach would likely have altered the outcomes in prior decisions

The intra-court methodological conflict across the writings is stark and measurable. The phrase “major questions” and “clear congressional authorization” function as decisive analytical tools for Roberts, Gorsuch, and Barrett. Kagan explicitly states those tools are unnecessary. Jackson relies on legislative history that Gorsuch expressly cautions against. Kavanaugh argues the doctrine should not apply in this domain at all.

Opinions v. briefs: what was adopted, what was rejected

The merits briefs – the government’s opening brief, the state challengers’ brief, and the private challengers’ brief (Learning Resources) – are also telling. Here is what the court adopted and what it rejected from each side.

What the court adopted (from the challengers’ briefs):

- Tariffs as taxing power. The challengers argued that tariffs are “a branch of the taxing power” and therefore categorically different from regulatory tools granted to the president like quotas and embargoes. The Roberts opinion of the court adopted this framing directly.

- Major questions applies; no emergency exception. The challengers argued the claimed authority is “breathtaking” and “unprecedented” and requires clear statutory authorization. The plurality adopted this framing and expressly held there is no emergency-statute carveout.

- No foreign-affairs exception to the major questions doctrine. The challengers argued the foreign-affairs context does not flip the interpretive presumption. The plurality agreed and rejected the government’s proposed carveout here.

- The lack of historical precedent is telling. No president had used IEEPA for tariffs in fifty years. The plurality treated this as an affirmative indicator against the government’s reading.

What the court rejected (from the government’s brief):

- The “poles/spectrum” theory. The government argued “regulate” sits between “compel” and “prohibit,” capturing less extreme tools including tariffs. The majority rejected this directly, finding tariffs “operate directly on domestic importers to raise revenue” and are not simply a milder embargo.

- Both anti-major questions doctrine carveouts. The government argued the major questions doctrine should not apply to emergency statutes and that foreign affairs context flips the interpretive presumption. Again, both were expressly rejected.

Argument volume and opinion length

The argument-to-opinion correlation is strongest for the justices who wrote extensively. Gorsuch and Kavanaugh both asked high volumes of doctrinal-framing and precedent-confrontation questions at argument, and both produced long written opinions anchored in the same frameworks they were probing. Barrett asked the highest volume of questions but produced the shortest concurrence; her argument questions focused on clarifying the scope of precedent and the nature of the major questions doctrine, and her brief writing addresses exactly those questions. Kagan and Thomas asked the fewest questions; Kagan’s concurrence is brief and methodologically focused, consistent with having entered argument already confident in her path.

In other words, what the justice asked at argument reflected the case’s final outcome.

How well did my prior prediction hold up?

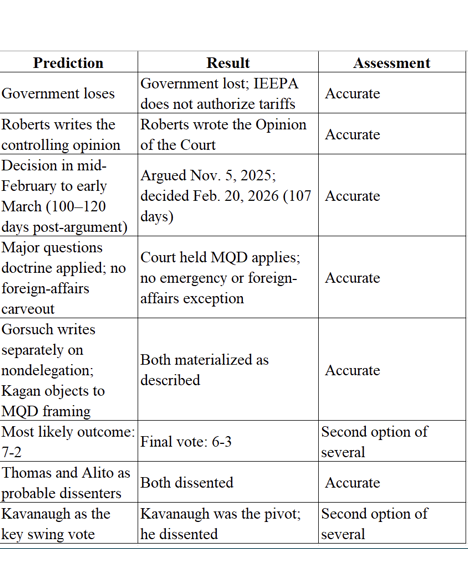

In a Legalytics piece, “The $133 Billion Question: Inside the IEEPA Tariff Case,” I made a series of empirical predictions:

The bottom line: my core predictions held. The vote count and Kavanaugh’s position were both secondary possibilities, and the length of the opinion correlation with why it took longer than expected seems correct as well.

What comes next: refunds and remaining uncertainty

The court’s holding resolves the question of whether the president has statutory authority to impose tariffs under IEEPA. It does not resolve the refund question; the opinion does not set out a refund mechanism, does not order restitution, and does not address the administrative processes by which duties already paid might be recovered.

Indeed, the only explicit discussion of refunds in the slip opinion appears in Kavanaugh’s dissent. He warns that the United States “may be required to refund billions of dollars to importers who paid the IEEPA tariffs,” and describes the refund process as likely to be a “mess” — citing the oral argument transcript for that characterization. He also flags the pass-through problem: whether importers who passed tariff costs to consumers can recover at all.

That the refund discussion is concentrated entirely in the dissent, rather than anywhere in the majority’s rule statement, is itself a meaningful feature of the opinion: the court resolved the legal question of authority and left the remedial mechanics entirely to future proceedings.