American diplomats in at least two countries have recently delivered internal reports to Washington that reflect a grim new reality taking hold abroad: The Trump administration’s sudden withdrawal of foreign aid is bringing about the violence and chaos that many had warned would come.

The vacuum left after the U.S. abandoned its humanitarian commitments has destabilized some of the most fragile locations in the world and thrown refugee camps further into unrest, according to State Department correspondence and notes obtained by ProPublica.

The assessments are not just predictions about the future but detailed accounts of what has already occurred, making them among the first such reports from inside the Trump administration to surface publicly — though experts suspect they will not be the last. The diplomats warned in their correspondence that stopping aid may undermine efforts to combat terrorism.

In the southeastern African country of Malawi, U.S. funding cuts to the United Nations’ World Food Programme have “yielded a sharp increase in criminality, sexual violence, and instances of human trafficking” within a large refugee camp, U.S. embassy officials told the State Department in late April. The world’s largest humanitarian food provider, the WFP projects a 40% decrease in funding compared to last year and has been forced to reduce food rations in Malawi’s sprawling Dzaleka refugee camp by a third.

To the north, the U.S. embassy in Kenya reported that news of funding cuts to refugee camps’ food programs led to violent demonstrations, according to a previously unreported cable from early May. During one protest, police responded with gunfire and wounded four people. Refugees have also died at food distribution centers, the officials wrote in the cable, including a pregnant woman who died under a stampede. Aid workers said they expected more people to get hurt “as vulnerable households become increasingly desperate.”

“It is devastating, but it’s not surprising,” Eric Schwartz, a former State Department assistant secretary and member of the National Security Council during Democratic administrations, told ProPublica. “It’s all what people in the national security community have predicted.”

“I struggle for adjectives to adequately describe the horror that this administration has visited on the world,” Schwartz added. “It keeps me up at night.”

In response to a detailed list of questions, a State Department spokesperson said in an email: “It is grossly misleading to blame unrest and violence around the world on America. No one can reasonably expect the United States to be equipped to feed every person on earth or be responsible for providing medication for every living human.”

The spokesperson also said that “an overwhelming majority” of the WFP programs that the Trump administration inherited, including those in Malawi and Kenya, are still active.

But the U.S. funds the WFP on a yearly basis. For 2025, the Trump administration so far hasn’t approved any money in either country, forcing the organization to drastically slash food programs.

In Kenya, for example, the WFP will cut its rations in June down to 28% — or less than 600 calories a day per person — a low never seen before, the WFP’s Kenya country director Lauren Landis told ProPublica. The WFP’s standard minimum for adults is 2,100 calories per day.

“We are living off the fumes of what was delivered in late 2024 or early 2025,” Landis said. On a recent visit to a facility treating malnourished children younger than 5, she said she saw kids who were “walking skeletons like I haven’t seen in a decade.”

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has pledged to restore safety and security around the world. At the same time, his administration, working alongside Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, swiftly dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, canceling thousands of government-funded foreign aid programs they considered wasteful. More than 80% of USAID’s operations were terminated, which crippled lifesaving humanitarian efforts around the world.

Musk, who did not respond to a request for comment, has said that DOGE’s cuts to humanitarian aid have targeted fraudulent payments to organizations but are not contributing to widespread deaths. “Show us any evidence whatsoever that that is true,” he said recently. “It’s false.”

For decades, American administrations run by both parties saw humanitarian diplomacy, or “soft power,” as a cost-effective measure to help stabilize volatile but strategically important regions and provide basic needs for people who might otherwise turn to international adversaries. Those investments, experts say, help prevent regional conflict and war that may embroil the U.S. “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition,” Jim Mattis, who was defense secretary during Trump’s first administration, told Congress in 2013 when he led U.S. Central Command.

Food insecurity has long been closely linked with regional turmoil. But despite promises from Secretary of State Marco Rubio that lifesaving operations would continue amid widespread cuts to foreign aid, the Trump administration has terminated funding to WFP for several countries. Nearly 50% of the WFP’s budget came from the U.S. in 2024.

Since February, U.S. officials throughout the developing world have issued urgent warnings forecasting that the Trump administration’s decision to suddenly cut off help to desperate populations could exacerbate humanitarian crises and threaten U.S. national security interests, records show. In one cable, diplomats in the Middle East communicated concerns that stopping aid could empower groups like the Taliban and undermine efforts to address terrorism, the narcotics trade and illegal immigration. The shift may also “significantly de-stabilize the transitioning” region and “only serve to benefit ISIS’ standing,” officials warned in other correspondence. “It could put US troops in the region at risk.”

Embassies in Africa have delivered similar messages. “We are deeply concerned that suddenly discontinuing all USAID counter terrorism-focused stabilization and humanitarian programs in Somalia … will immediately and negatively affect U.S. national security interests,” the U.S. embassy in Mogadishu, Somalia, wrote in February. USAID’s role in helping the military prevent newly liberated territory — “purchased at a high cost of blood and treasure” — from getting back into the hands of terrorists “is indisputable, and irreplaceable,” the officials added.

The embassy in Nigeria described how stop-work orders had caused lapses in oversight that put U.S. resources at risk of being diverted to criminal or terrorist groups. (A February whistleblower complaint alleged USAID-purchased computers were stolen from health centers there.) And U.S. officials said the Kenyan government “faces an impending humanitarian crisis for over 730,000 refugees” without additional resources, as local officials struggle to confront al-Shabaab, a major terrorist threat in the region, while also maintaining security inside the country’s refugee camps.

In early April, Jeremy Lewin — an attorney in his late 20s with no prior government experience who is currently in charge of the State Department’s Office of Foreign Assistance and running USAID operations — ordered the end of WFP grants altogether in more than a dozen countries. (Amid outcry, he later reinstated a few of them.) The State Department spokesperson said the agency was responding on Lewin’s behalf.

In Kenya, the WFP expects a malnutrition crisis after rations are cut to a fourth of the standard minimum, Landis said. She is also concerned about the security of her staff, who already travel with police escorts, given the likelihood that there will be more protests and that al-Shabaab might make further incursions into the camps.

In order for the U.S. to deliver its usual food aid to Kenya by the end of the year, it needed to be put on a boat already, Landis said. That has not happened.

Credit:

Courtesy of World Food Program/Kevin Gitonga

In recent days, South Sudanese refugees in Ethiopia have begged a visiting government delegation from the U.S. not to cut food rations any further, according to a cable documenting the visit. Aid workers in another group of camps in North Africa reported that they expect to run out of funding by the end of May for a program that fights malnutrition for 8,600 pregnant and nursing mothers.

Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world, Malawi has been a relative beacon of stability in a region that’s seen numerous civil wars and unrest in recent decades. Yet in early March, officials there warned Washington counterparts that cuts to the more than $300 million USAID planned to provide to the country in aid a year would dramatically increase “the effects of the worsening economy already in motion.”

At the time, 10 employees from a USAID-funded nonprofit had recently shown up unannounced at USAID’s offices in the capital Lilongwe asking for their unpaid wages after the U.S. froze funding. The group left without incident, and it’s unclear if they were paid, but officials reported that they expected countries around the world would face similar issues and were closely monitoring for “increased risks to the safety and security of Embassy personnel.” (Former employees at another nonprofit in a nearby country also raided their organization “out of desperation for not being paid,” according to State Department records.)

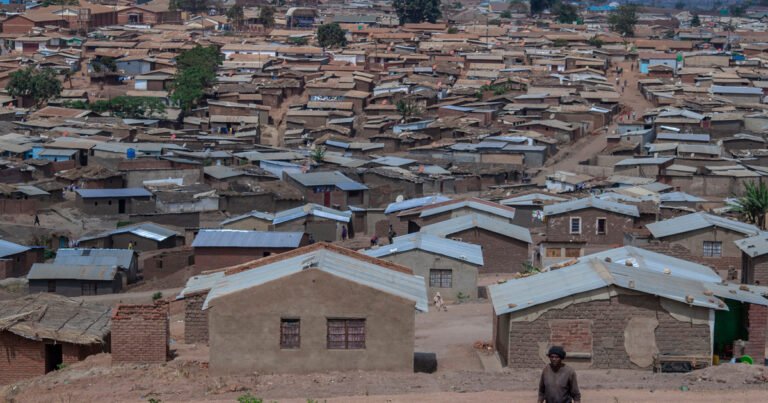

An hour’s drive from the nation’s capital, Dzaleka is a former prison that was transformed into a refugee camp in the 1990s to house people fleeing war in neighboring Mozambique. In the decades since, it has ballooned, filling with people running from conflicts in Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. The camp, which was built to hold around 10,000, is now home to more than 55,000 people.

Credit:

African Media Online/Alamy Stock

Iradukunda Devota, a refugee from Burundi, came to Malawi when she was 3 and has lived at Dzaleka for 23 years. She now works for Inua Advocacy, which provides legal services and advocates on behalf of refugees in the camp. She said tension is high amid rumors that food and other aid will be cut further. Since 2023, the Malawi government has prohibited refugees from living or working outside the camp, and there has already been an increase in crime and substance abuse after food was cut earlier this year. “This is happening because people are hungry,” Devota told ProPublica. “They have nowhere to turn to.”

Now, the Malawi government is likely to close its borders to refugees in response to the funding crisis and congestion in Dzaleka, the WFP’s country representative told the State Department, according to agency records.

Diplomats continue to warn the Trump administration of even worse to come. The WFP expects to suspend food assistance in Dzaleka entirely in July.

“The WFP anticipates violent protests,” the embassy told State Department officials, “which could potentially embroil host communities and refugees, and targeting of UN and WFP offices when the pipeline eventually breaks.”

ProPublica plans to continue covering USAID, the State Department and the consequences of ending U.S. foreign aid. We want to hear from you. Reach out via Signal to reporters Brett Murphy at +1 508-523-5195 and Anna Maria Barry-Jester at +1 408-504-8131.