If you’re requesting emergency relief from the Supreme Court, how long should you expect to wait for a decision? In other words, does the court really treat emergency applications as emergencies? The answer, it turns out, depends on what kind of emergency you have. Decision times for the court’s emergency, or interim relief, docket have evolved dramatically over the past decade, but not uniformly. Some applications move through in days, while others take months.

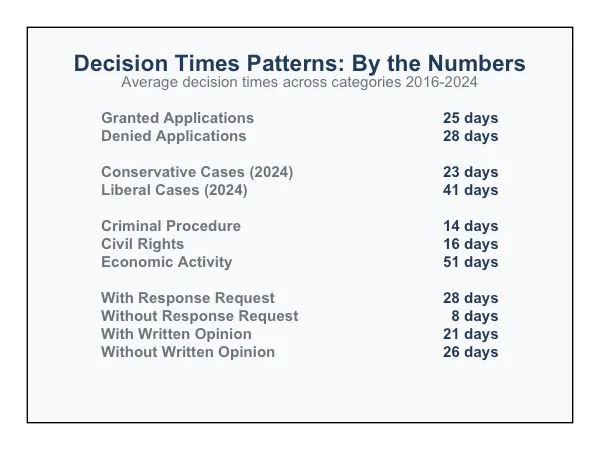

Perhaps most striking is that speed correlates with the political direction of cases. In 2024, cases with conservative outcomes averaged 23 days to decide, while cases with liberal outcomes took 41 days – a 76% difference that reveals how the court’s approach to emergency relief is often influenced by a case’s ideological outcome.

Some background

As detailed in my last article, applications on the interim relief docket – used to describe cases in which a party comes to the court for an order on an emergency basis without full briefing and oral argument – can be broken into three categories. First, there are the death penalty cases, which traditionally made up the bulk of the interim relief docket. Specifically, these are requests for the Supreme Court to pause an execution (or allow an execution that is currently paused to go forward).

Second, there are emergency applications that are refiled, or filed first with one justice and then another. These applications are almost always distributed for the court’s conference, considered by the full court, and then denied.

Finally, there are substantive applications, which involve the core work of emergency relief (and get the bulk of media attention). These include such matters as judicial power cases (challenging courts’ authority to constrain executive action), administrative state disputes (like EPA regulatory enforcement), First Amendment conflicts, and federalism questions about the conflict between state and federal authority.

This analysis examined decision times for emergency applications from the beginning of the court’s 2016-17 term through Aug. 25, 2025, tracking the days from initial filing to the final order. It found that death penalty cases follow predictable patterns; they averaged between two and six days across all terms, and most were decided within 24 hours. Refiled applications usually took between 60 and 80 days as they worked through the court’s conference procedures before inevitably being denied. The patterns in the substantive applications tell a different story, however: in such cases, emergency relief has evolved from a relatively uniform process into one with distinct patterns based on a case’s characteristics. As I describe below, decision times now vary by a case’s ideological direction, its subject matter, and its complexity.

Decision times trends for substantive applications

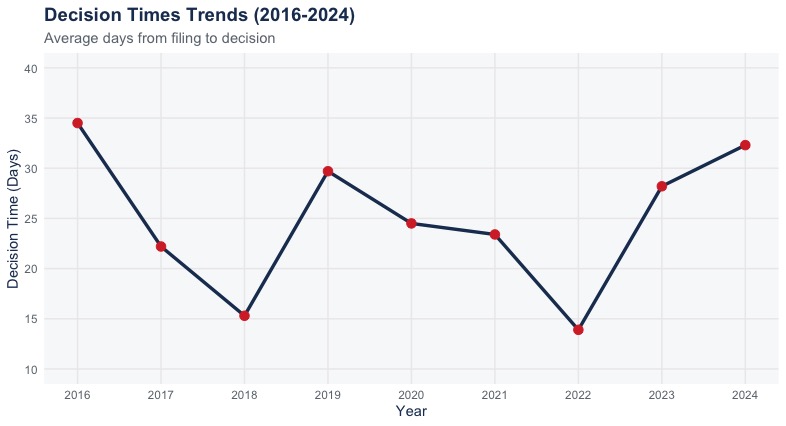

Decision times for substantive emergency applications have followed an erratic path over the past decade. In the 2016-17 term, the processing time for these cases averaged 35 days – hardly “emergency” speed, even then. By the 2018-19 term, the court found its “rhythm,” and decision time accelerated to 15 days. But that efficiency proved temporary. Decision times climbed back to nearly 30 days by the 2019-20 term and have (generally) remained elevated since.

During the 2024-25 term, the average decision time for emergency applications was just over 32 days, nearly the same amount of time it took the court to deal with emergency applications during the 2016-17 term. In other words, the court hasn’t gotten any more efficient over time, it turns out, at deciding emergency applications.

We do see a blip on the screen in the 2022-23 term, when decision times dropped to just 14 days, the fastest in the last decade. It appeared the court had made strides in processing requests for emergency relief. But that term also had the lowest caseload of substantive emergency applications at 25 cases. When volume more than doubled to 53 substantive emergency applications during the 2023-24 term, decision times nearly doubled too, jumping to 28 days.

The ideological influence on emergency applications

But we can dig a little deeper. And when we do so, we come across something even more striking: The ideological direction of Supreme Court decisions on emergency applications now predicts how quickly they are decided. In 2024, liberal cases took an average of 41 days to be decided while conservative cases averaged 23 days – a dramatic 76% difference based purely on ideology.

Interestingly, this has not always been the case. In the 2016-17 term, the pattern actually favored liberal outcomes, with applications with conservative outcomes taking 37 days to decide compared to just nine days for liberal ones. The gap narrowed through the late 2010s, reaching near-parity by the 2020-21 term, when conservative cases averaged 29 days to decide and liberal cases 24 days. But since then, the divergence has accelerated dramatically.

The data offers only limited insight into the reason for this gap. The types of applications and whether a justice requested a response in a case are nearly identical across ideological directions. We don’t know the court’s internal reasoning, of course. But several factors could be contributing to this pattern. Most obviously, cases that ultimately produce conservative outcomes may present legal questions or policies that align more with the current court’s jurisprudence. As the court has become increasingly conservative, such cases would thus require less deliberation among the justices. Conversely, cases that result in liberal outcomes might require more internal discussion to reach a decision.

The type of case also makes a difference

The data also shows significant variation in decision times across different types of legal disputes. Criminal procedure and civil rights cases moved through the system fastest, averaging 14-16 days. At the other extreme were economic activity cases, which averaged 51 days – more than triple the processing time for the fastest categories. This broad category, involving business regulation, economic policy disputes, and commercial matters, consistently received lengthier consideration. Indeed, the five slowest cases in the dataset all fell into this category, each having taken 82-85 days to resolve.

Other issue areas fell between these extremes: First Amendment cases averaged 20 days, judicial power disputes took 21 days, due process claims required 26 days, and federalism questions averaged 31 days.

These patterns persist regardless of which party seeks relief or who occupies the White House. Economic cases moved slowly under both the Biden and Trump administrations, for example. What this does point to is that the court appears to view some types of legal disputes as inherently more urgent than others, with the time to reach a decision serving as a form of substantive commentary on the relative importance of different areas of law.

Other findings

Several other things stood out. First, from 2016-2019, emergency applications that were granted were decided faster than those that were denied, sometimes dramatically so (in the 2019-20 term, granted cases averaged nine days versus 44 days for denials). But that pattern has become inconsistent in recent years. In the 2023-24 term, granted cases took longer (36 days) than denied cases (26 days). But by the 2024-25 term, the pattern had reversed again, with granted cases averaging 23 days versus 40 days for denials.

Second is the impact of response requests on decision times. What were once rare exceptions – the justices only requested a response from parties in complex cases requiring additional briefing – have become the norm, occurring in 96% of emergency applications from 2022 through the period studied. When a justice requests a response, it adds an average of 20 days to processing time compared to eight days for those few cases that proceed without responses. The court has thus quietly transformed emergency procedures into something resembling regular litigation, complete with briefing schedules.

Finally, emergency application decisions with written opinions don’t consistently take longer to process, contradicting assumptions about deliberation and speed. Across the full dataset, cases with written opinions averaged 21 days compared to 26 days for cases without opinions – in other words, and counterintuitively, those cases with written opinions were actually decided faster. This may be because the court writes opinions for cases in which they reach consensus in short order, and then seeks to document the justices’ reasoning quickly so as to avoid extended deliberation.

The bottom line

Perhaps the biggest takeaway is this: The Supreme Court’s so-called emergency docket isn’t really for emergencies. What should be urgent relief routinely takes weeks or months. What’s more, the court has developed a two-speed system, with ideology and case type influencing the time in which a case is decided.

Recommended Citation:

Taraleigh Davis,

Is the emergency docket really for emergencies?,

SCOTUSblog (Sep. 16, 2025, 9:30 AM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/09/is-the-emergency-docket-really-for-emergencies/