I’ve defended plenty of white-collar crimes throughout my career. For some, the phrase evokes images of high-status business professionals engaging in fraud for financial gain. For me and many others who defend the criminally accused, though, white-collar crimes refer to any nonviolent financial criminal allegation.

For most folks, “love cons” or “romance scams” rarely come to mind. Which is why Netflix’s Love Con Revenge is an important, if flawed, offering in the true-crime genre.

Romantic manipulation for monetary gain

The six-episode series follows private investigator Brianne Joseph and Cecillie Fjellhøy, who was the victim of another romance scam detailed on Netflix’s Tinder Swindler. The two women interview victims of fraud perpetrated by bad actors who romantically manipulate individuals for their own financial gain.

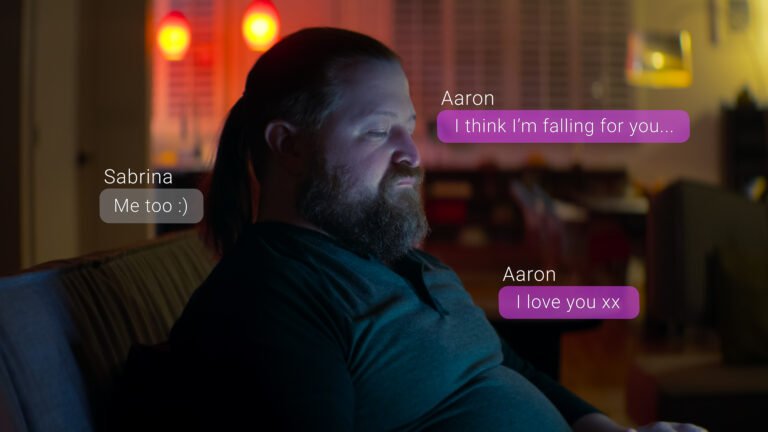

Jumping into the fifth episode was disjointing. I had to double-check to ensure I hadn’t accidentally skipped the beginning, because I was immediately dropped into the middle of a story involving Aaron, a man who had been conned out of approximately $100,000 by a scammer named Sabrina.

Aaron was not her only victim. In fact, by the time the production team introduces Sabrina to the audience, she has already been charged by the FBI and convicted of wire fraud. Much of the discussion centers not only on Sabrina’s actions and their impact on Aaron, but also the fact that the FBI did not list Aaron as a victim in Sabrina’s case. Joseph meets with an FBI agent involved in the prosecution, who informs her that the agency couldn’t include Aaron’s allegations because there is a five-year statute of limitations for federal wire fraud.

Spending the inheritance

Next the audience is introduced to Lindsay, a hairstylist who recounts her experiences with Chris, a person she met on Tinder. They quickly fell for each other, or so she thought.

Within a relatively short amount of time, Chris convinces Lindsay to transfer funds she received from her late mother’s 401(k). He said he could use his skills as a financial adviser to get her a 10% return on the funds. After she receives one check from him, the relationship starts to fizzle out, and she sets out to try and reclaim the funds she transferred to him.

The episode ends with the hosts heading off to find another one of Chris’ potential victims; she was discovered through an online record regarding a restraining order against him. They discuss how the situation must have been serious, because, according to Fjellhøy, “a restraining order … is not something that courts grant lightly.”

Statistics and statutes (of limitation)

Apparently, the Love Con Revenge episodes run fluidly, with one leading into the other. Each episode ends on a “cliffhanger,” and the next installment immediately picks up where the last episode left off.

Which explains the confusion I felt in starting with an episode in the middle of the series. This odd method of storytelling would have been nice to know going into the viewing experience, but that is just one of the series’ many failings.

The production is far too contrived. As someone who has spent years analyzing various true-crime documentaries and series, it was painfully obvious that Love Con Revenge was heavily scripted and lacked much genuine empathy and emotional impact. Every conversation comes off as orchestrated, and it’s challenging to connect with the victims.

Additionally, the “investigation” performed doesn’t amount to much. Perhaps that’s the best takeaway from the series, though: The general public has a wealth of information at their fingertips; it’s not that difficult to run a web search on someone or perform a reverse image search if you are looking to find out more about someone you met online.

I was also extremely unimpressed with the discussion regarding the applicable statute of limitations. I agree with the blanket assertion that the federal government has five years from the date of the criminal activity to move forward with wire fraud charges, but in some situations, there are specific exceptions that can toll a statute of limitations. The applicable legal principles aren’t always as unequivocal as the episode would suggest, and further discussion would have been helpful.

In some jurisdictions, and with regard to certain causes of action, the discovery rule allows the clock to start ticking on the statute of limitations when the issue is actually discovered or, in other cases, when the subject matter could have been discovered through the victim’s reasonable diligence. During the Love Con Revenge episode I viewed, there was absolutely no discussion about this exception.

Restitution and the rarity of repayment

There is a throwaway statement mentioning that Sabrina, as a part of her plea agreement, has to make an effort to pay everyone back. But is no mention of “restitution” or what that amounts to, or how that can impact a defendant’s probation.

In most cases, restitution will be part and parcel with a plea agreement or a condition of the sentence upon conviction. For that reason, it is rare to find a white-collar case resolution that doesn’t include at least some form of probation on the back end, even if the defendant is ordered to complete a term of incarceration. The probation after the fact allows for an enforcement mechanism for restitution collection.

Still, as the old saying goes, you can’t get blood from a turnip. In most cases where money has been stolen through fraud, it’s surprising how often that money is already spent by the time the crime is formally charged. As such, it’s very common for victims of these financial crimes never to receive the total they have lost. So in situations like Aaron’s, even if his loss was formally filed in court, there’s no guarantee he would have received even a portion of the $100,000 he gave away.

After all, if incarceration is a court’s only recourse against a defendant who will not or cannot pay restitution, those defendants aren’t going to pay any more than they would otherwise while sitting in prison.

Ultimately, I wouldn’t recommend the series. Nevertheless, if even one person learns to be a bit more cautious and skeptical of the strangers they meet online, it’s probably worth it to potentially lower the $1 billion lost to these types of scams in the U.S. every year.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seem to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.