Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

The Supreme Court’s next two weeks of oral arguments are set to begin, and it will be telling to see if they resemble the court’s first round of oral arguments, which took place in October. Perhaps most interestingly, throughout these arguments, the justices were more interested in how cases get decided than in making sweeping new rules. We will see if this is an anomaly or a theme of this term.

Procedure over big ideas

Unlike decisions on the court’s emergency docket, which arrive with little explanation, oral arguments let us watch the justices think through tough cases in real time. This October’s early cases – covering everything from criminal trials to lawsuits against the postal service – showed a court focused on practical questions: Who can sue? What can a court actually order others to do? Will this rule work when a judge has to apply it at midnight?

Take Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections, in which the court considered whether a candidate had a legal right to challenge an election law allowing certain mail-in ballots. In that case, Justice Brett Kavanaugh cut straight to the potential consequences: “What’s the remedy … Do you throw out those votes?”

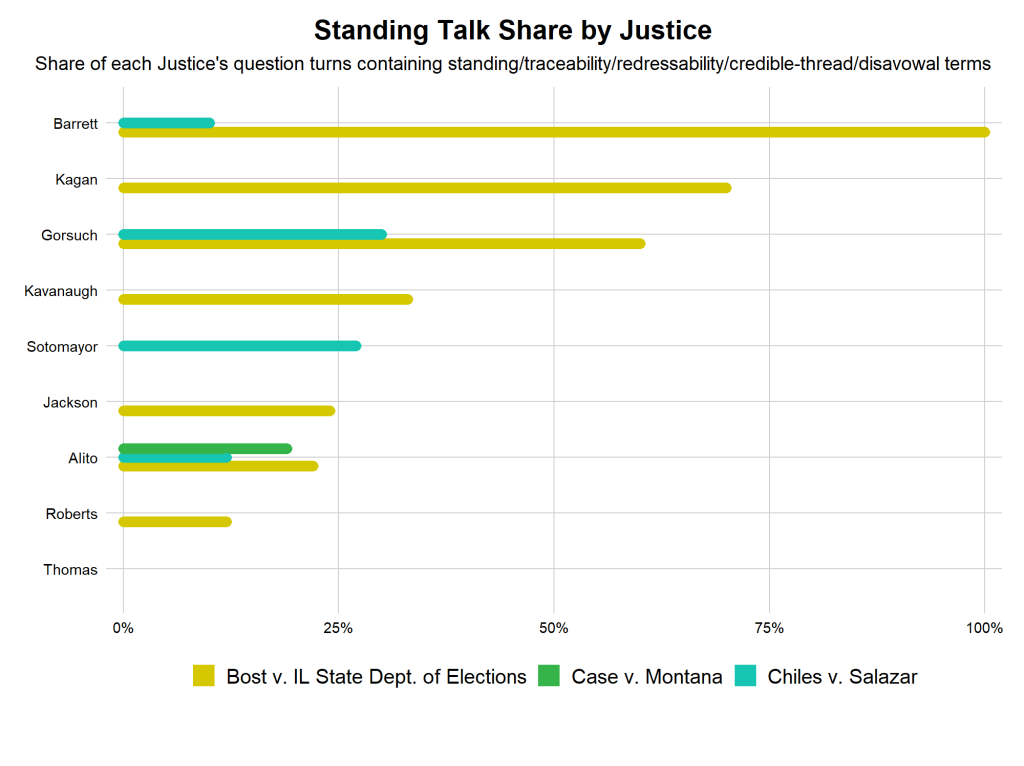

And in Chiles v. Salazar, the challenge to Colorado’s ban on “conversion therapy,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor pressed the lawyer for Kaley Chiles, the Colorado therapist challenging the law, on whether she had anything concrete to complain about when the state had already promised not to enforce the law: “They’ve disavowed it. How does that give you standing?”

Along these lines, the data shows that words like “injury,” “traceable,” and “concrete harm” dominated early questioning from Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan, and Brett Kavanaugh.

Who gets through the door

As noted, a large chunk of argument time in October focused on procedural matters – who may be in federal court and under what conditions. Some cases, such as Bowe v. United States, involved rules about when federal prisoners can challenge their convictions. Others, such as Berk v. Choy, turned on when state rules apply in federal court.

These aren’t minor housekeeping matters. The prison cases determine whether inmates get a second look at their convictions. Other disputes will determine whether state requirements – like needing a doctor’s sworn statement to sue for medical malpractice – can reshape how you file a lawsuit in federal court.

The likely outcome in such cases is a narrow, manageable ruling rather than a sweeping new principle.

When words pile up

One case, United Postal Service v. Konan, offered a clean test of how justices read laws. The relevant statute at issue uses three terms – “loss,” “miscarriage,” and “negligent transmission” – and a question was whether Congress meant each to mean something different or whether they all point to the same idea.

Two camps emerged. Some justices invoked the rule that every word in a law should mean something distinct: If Congress used three terms, they must have meant three different things. Justice Neil Gorsuch pressed this point: “there is still [extra language] there … certainly with ‘miscarriage.’”

Other justices offered a more practical reading: these are just different ways of saying the U.S. Postal Service lost or mishandled your mail. Kagan read them as a unit: “they’re losing your letters … negligently transmitting … miscarrying … the same kind of meaning.”

The tolerance for overlap will shape several other cases this term, where the outcome may turn less on grand theory than on how much wiggle room the justices think the law allows.

Rules that work in courtrooms

The criminal cases also asked the court to draw practical lines that can be used in courtrooms: Can prosecutors ask what a defendant discussed with his lawyer during an overnight break? What counts as urgent enough to enter a home without a warrant?

In the overnight-break case, Villarreal v. Texas, the lawyer representing a Texas man who contends that the trial court violated his constitutional right to the assistance of counsel when it barred him from speaking with his defense lawyer during an overnight break emphasized the practical stakes: “During an overnight recess, the defendant and his counsel have a lot that they need to talk about. … These are basic discussions that any competent lawyer would have with a client.” Some justices then pressed how to protect that right without letting defendants lie on the stand. The question wasn’t about theory – it was about what trial judges do when the jury goes home for the night.

The home-entry case, Case v. Montana, turned on rules that officers need to apply when they believe an emergency is occurring inside a home. Whatever the court decides will serve as a field manual for officers deciding whether they need to obtain a warrant in certain home entries.

Justice by justice

A closer look at the justices reveals their particular areas of focus during the first two weeks of oral argument.

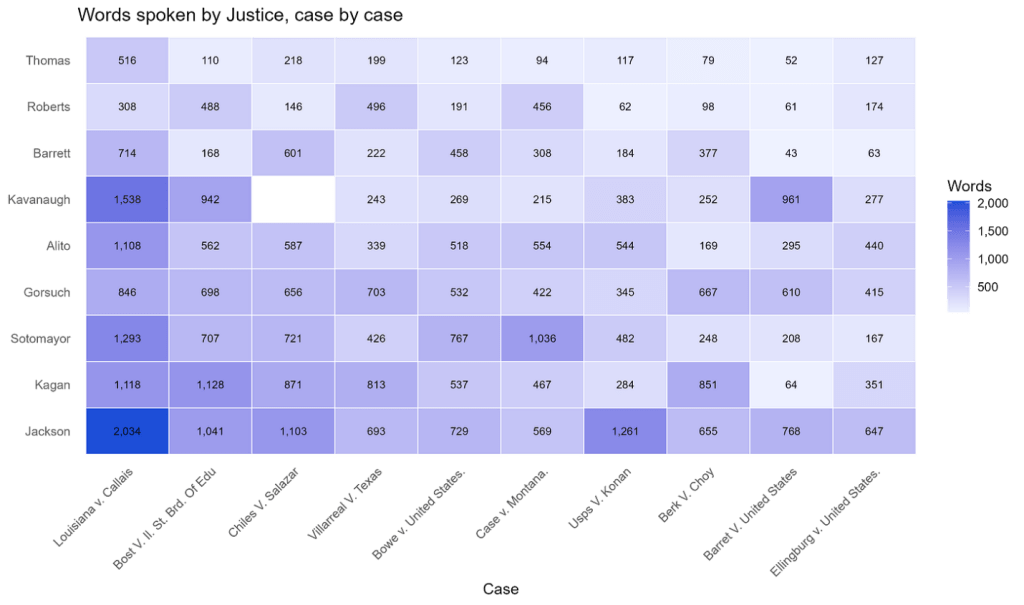

As the chart above illustrates, Jackson led in the most contentious case of the session, Louisiana v. Callais, concerning the constitutionality of racial redistricting, in which she did 21% of the total questioning.

In the home-entry case, Sotomayor dominated the discourse, often pressing how standards would work when officers have seconds to decide. Jackson and Kagan were also focused on practical issues in the criminal cases such as cross-examination, jury instructions, and trial errors. All of these justices were testing whether proposed rules would actually function in practice.

Kavanaugh’s most striking focus came in Barrett v. United States, a firearms-sentencing case concerning double jeopardy (31% of the questioning), in which he concentrated on what the statute at issue actually says.

Gorsuch figured prominently in both the federal-state procedural case (20% of the questioning) and the U.S. Postal Service dispute. In both, his textualist bona fides came to the fore, as he pressed: What does the text permit, and where are courts stretching it?

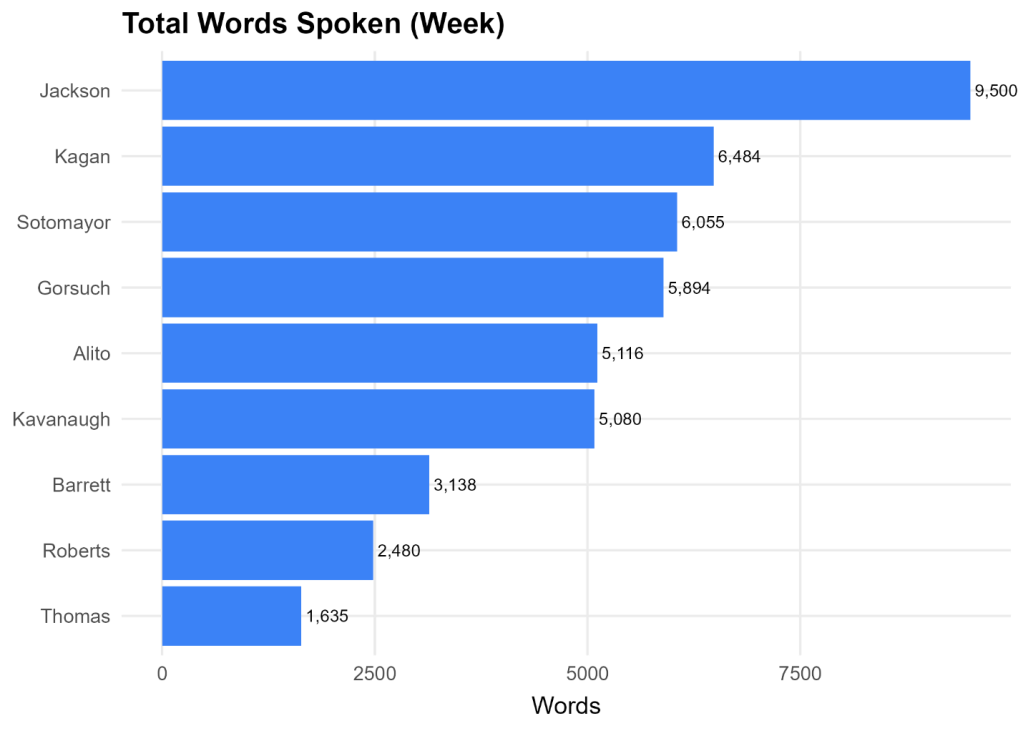

Jackson spoke the most words overall (see below), with Kagan close behind and Sotomayor third. But word count alone doesn’t tell the full story. Kagan took the longest turns, followed by Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Jackson. These justices used extended questions to explore alternatives and challenge lawyers on different interpretations. The chief justice kept the shortest turns – a style aimed at narrowing issues and moving things along. Gorsuch and (especially) Justice Clarence Thomas were similarly brief.

What this may reveal about the term ahead

Oral argument exposes the fault lines on the court, such as which justices care the most about who can bring a suit, who pays the most attention to text, and who presses the hardest on real-world consequences.

What emerges is not a unified court but a collection of justices with distinct concerns. When standing and remedies dominated, Jackson and Kagan led the questioning. When the text was in tension with the practical consequences, Gorsuch and Jackson framed the poles – one insisting on textual precision, the other asking what the claim is really about –while Kagan worked to mediate between the two sides. In criminal cases, Sotomayor, Jackson, and Kagan concentrated on usable standards; Chief Justice John Roberts and Gorsuch pressed how those standards would operate.

These patterns matter because the court’s October arguments often preview the term. A court that opens by front-loading threshold questions, testing remedies before reaching merits, and asking whether proposed rules will work in practice is a court preparing to decide narrowly when it can.

Above all else, the first two weeks suggest the court is taking its time – pressing for workable standards and showing more interest in how decisions will be applied than in how they’ll read in textbooks. Whether that caution holds as more politically charged cases arrive remains to be seen.

Cases: Louisiana v. Callais (Voting Rights Act), Louisiana v. Callais, United States Postal Service v. Konan, Berk v. Choy, Chiles v. Salazar (Conversion Therapy), Bowe v. United States, Villarreal v. Texas, Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections, Barrett v. United States, Case v. Montana

Recommended Citation:

Adam Feldman,

What can we learn from the Supreme Court’s first round of oral arguments?,

SCOTUSblog (Nov. 3, 2025, 9:30 AM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/11/what-can-we-learn-from-the-supreme-courts-first-round-of-oral-arguments/