Cases and Controversies is a recurring series by Carolyn Shapiro, primarily focusing on the effects of the Supreme Court’s rulings, opinions, and procedures on the law, on other institutions, and on our constitutional democracy more generally.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

Earlier this month, I wrote about the court’s opinion in Trump v. CASA and why it is, in my view, very problematic. But at least it was an opinion. In too many other cases, the court has provided no explanation at all for granting emergency applications filed by the Trump administration.

Recently, for example, in McMahon v. New York, on an apparent 6-3 vote, it stayed an injunction that would have stopped the administration from dismantling the Department of Education, a congressionally created agency. And in Trump v. American Federation of Government Employees, on an apparent 8-1 vote, the court stayed an injunction that would have stopped the government from planning for a massive series of reductions in force in numerous agencies. The majority gave no reasons for these stays. That’s been true in about half of the cases in which the court has stayed lower court injunctions and orders on an emergency basis at the request of the Trump administration.

Many commentators have criticized the court’s failure to explain its rulings in these and other cases, as have the dissenting justices. The court’s silence leaves district courts and litigants with no guidance about what particular aspects of the stayed injunctions were problematic. In some cases, the district courts issued pages and pages of factual findings, but we (and they) have no way of knowing if the court considers some of them likely to be clearly erroneous or in some way irrelevant. In some cases, the lower courts included significant legal analysis, but we (and they) don’t know with what, if anything, the court disagrees. In Department of Homeland Security v D.V.D., in which the government is sending noncitizens to countries they have no connection to and that may be dangerous for them, the Supreme Court even appears to be rewarding the government’s gamesmanship in its appeals, but without an explanation, we can’t know if the majority took the administration’s conduct into account.

If a district court were to grant a preliminary injunction – the standard for which largely tracks the standard for a stay – without saying why, reviewing courts, including the Supreme Court, would likely determine that the district court had abused its discretion and, at a minimum, would remand the case for an explanation. So why isn’t the majority holding itself to the same standard? Why is it so often silent as it grants emergency relief to the Trump administration?

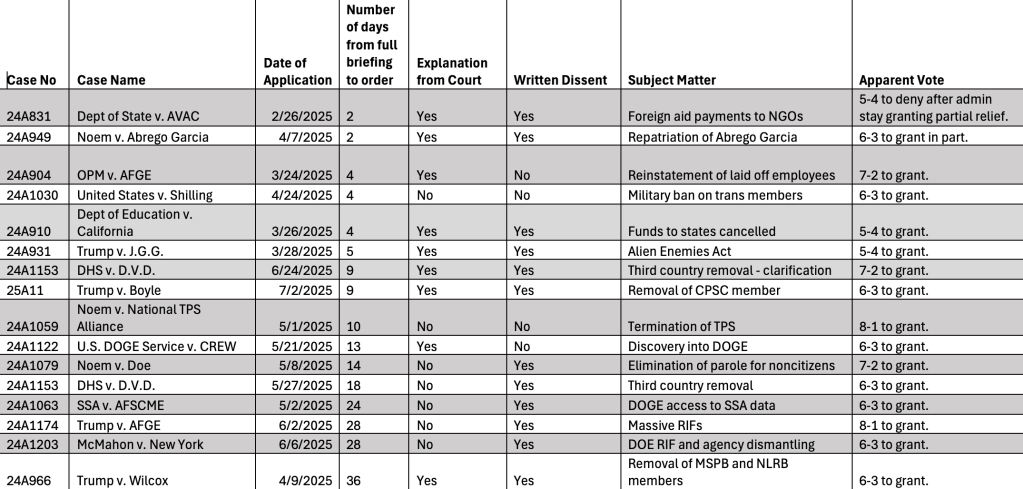

Maybe it’s because the majority itself does not have a common rationale for the rulings. Of course, that’s a theory I can’t verify. But the pace of the cases in which the court has provided emergency relief to the government is suggestive. As the table below indicates, the court has generally taken longer – sometimes weeks longer – to issue its rulings in cases where it provides no explanation. One might expect the opposite – that the court would be more likely to provide an explanation when it takes more time than when it rules very quickly. This somewhat surprising pattern suggests the possible inference that in the cases with no reasons given, the majority has struggled unsuccessfully to find a common rationale and has given up.

Note: This table does not include (1) Trump v. CASA because the court ordered oral argument in that case, treating it very differently from other emergency applications; (2) Bessent v. Dellinger, which was filed on Feb. 16 and fully briefed by Feb. 19, because the court held it in abeyance and then dismissed it as moot based on developments in the lower courts, and (3) National Institutes of Health v. American Public Health Association, filed on July 24, because it is neither fully briefed nor decided.

In the early rounds of emergency applications that the Trump administration brought to the Supreme Court, the court acted very quickly. The table lists seven emergency applications that the government filed before May. In six of those seven cases, the court issued an order between one and five days after the matter was fully briefed, granting at least some of the relief the government sought. (In one case, Trump v. Wilcox, in which the lower courts enjoined the president’s removal of members of the Merit Systems Protection Board and the National Labor Relations Board, the court took 36 days to rule – the longest of any emergency application. But in that case, the chief justice issued an administrative stay almost immediately, keeping the injunction from going into effect while the court considered the government’s application.)

And in all but one of those seven cases, including Wilcox, the court majority provided some kind of explanation or guidance to the district court, although it was generally very short. In the seventh case, United States v. Shilling, the court provided no explanation as it stayed an injunction that would have prevented the military from discharging its transgender servicemembers on an apparent 6-3 vote.

For the nine applications filed and ruled on since May 1, on the other hand, the court took at least nine and as many as 28 days to issue a ruling, and it gave any reason or guidance at all in only three. Indeed, for two of the most recent applications it granted, Trump v. AFGE and McMahon v. New York, the court took 28 days to rule after full briefing and provided no explanation whatsoever, despite robust dissents and, in AFGE, a brief concurrence by Justice Sonia Sotomayor explaining why she joined the majority.

Certainly, lack of agreement within the majority is not the only possible explanation for the pattern I’ve identified. As the end of June approaches, the justices and their law clerks are under a lot of pressure. It is the busiest time at the court, and attention is undoubtedly focused on other matters. But I don’t think that time pressure really can explain the longer waits and less explanation. After all, the orders in Trump v. AFGE and McMahon came 11 and 17 days, respectively, after the court issued its last opinions in merits cases on June 27. There was plenty of time for the majority to explain itself.

Another possible explanation for the longer timeframes, although not for the majority’s silence, is that both AFGE and McMahon had relatively lengthy dissents. So perhaps the majority was waiting for the dissenters to finish. But the court can and does occasionally issue orders with the promise of subsequent dissenting opinions or other separate statements by individual justices to come. It did just that in A.A.R.P. v. Trump when it ordered the government not to remove from the country any members of a putative class of noncitizens pursuant to the Alien Enemies Act, over Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas’ noted but unexplained dissents. (Alito subsequently issued an opinion explaining their views.) And one might think that the lengthy dissents in AFGE and McMahon would make the majority more, rather than less, inclined to explain itself. If it could reach consensus on its reasons, that is.

Even if I’m right about the majority’s inability to agree on a rationale, however, the court has options other than issuing unexplained stays. It could, for example, send the case back to the lower courts directing them to address particular legal or factual issues. It could schedule argument, as it did in Trump v. CASA, and/or call for additional briefing to focus on the justices’ areas of concern.

What it should not be doing is failing to provide even the views of individual justices who agree that a stay is appropriate. Individual justices can and should explain their positions in concurring opinions, including disclosure of disagreements within the majority. Indeed, even when Sotomayor concurred with the majority in Trump v. AFGE, she explained only why she thought the stay the court was issuing was not likely to irreparably harm the plaintiffs (which is not the correct standard for a stay pending appeal), not why she thought it should issue at all. And in two other cases, Noem v. Doe and Noem v. National TPS Alliance, Justice Elena Kagan, and in Doe, Sotomayor, apparently joined the majority without explanation.

Ultimately, a lack of agreement about why to grant a stay should give the justices pause about the action they are taking. Perhaps the majority worries that a fractured rationale would be more confusing than none at all. But if the public, the parties, and the lower courts would get no meaningful guidance from fractured opinions issued at the very preliminary stages of a case, that seems to me to be all the more reason for the case to proceed without the Supreme Court’s intervention, allowing facts and legal arguments to develop in the ordinary course. There may of course be cases where, despite internal disagreement over reasons, a stay is justifiable. But even such a conclusion can and should be explained. That’s what courts are supposed to do.

Cases: Department of Homeland Security v. D.V.D., Trump v. American Federation of Government Employees, McMahon v. New York, Trump v. CASA, Inc., Trump v. Wilcox

Recommended Citation:

Carolyn Shapiro,

When the majority disagrees on the shadow docket,

SCOTUSblog (Jul. 30, 2025, 12:10 PM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/07/when-the-majority-disagrees-on-the-shadow-docket/