AV Ristorante is a recurring series by Brian Fitzpatrick.

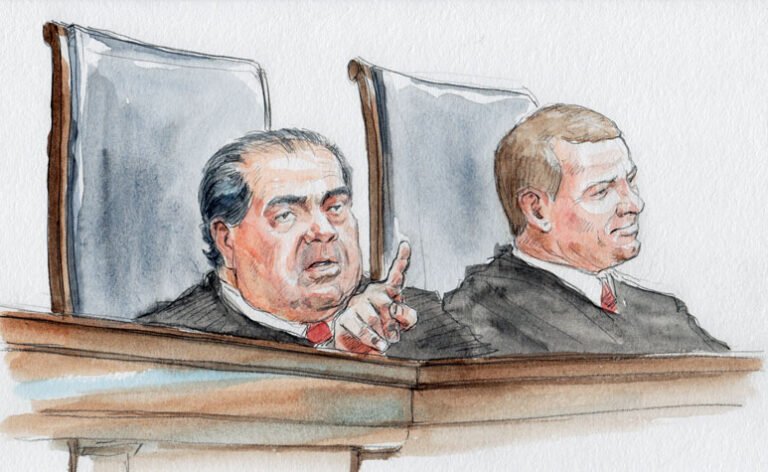

Ten years ago today, my old boss Supreme Court Justice Antonin “Nino” Scalia passed away. At the time of his death, it was clear that he was already one of the most influential justices ever to serve on the court. Today, this statement is even more true. No matter where you look – courtrooms, law firms, even law school classrooms – Scalia and his ideas are ubiquitous.

Scalia was not just a judge but a philosopher: he sought to fundamentally change how we think about the role of a judge in a democratic nation. His view was very simple: if the law is to change, it should be changed by the people who wrote the law, not by nine unelected judges sitting on the Supreme Court. If your favorite right is not in the Constitution, amend it. If your favorite provision is not in the U.S. Code, ask Congress to add it. If you can’t convince your fellow citizens that the law should change, why should you be able to get your way through judicial fiat instead?

He called this view “textualism” for statutes and “originalism” for constitutional provisions, but the two terms are synonymous: judges should follow the original understanding of a text until the text is changed. The idea is so compelling it is hard to believe it was ever controversial. But it was – until Scalia joined the Supreme Court in 1986.

Since then, textualism and originalism have taken over the legal profession. Even before Scalia passed away, studies showed that judges and lawyers started citing his favored materials (dictionaries, canons of interpretation, the Federalist Papers) to the exclusion of others (his bête noir: legislative history). These trends have only accelerated since then and have seeped into the state court systems as well. The trends are even bipartisan: one could argue that the best textualist on the Supreme Court today is Elena Kagan. As she admitted not too long ago, thanks to Justice Scalia, “[w]e’re all textualists now.” Although she might have taken a bit of artistic license there, no one doubts his philosophies command a majority on the Supreme Court and probably on the lower courts as well.

How do we know for sure Scalia is responsible for all this? He was not the first to embrace these views, and, as I noted, there are plenty of others who have embraced them since. But, as professor Frank Cross found in a study back in 2010 of federal lower court judges: “the most striking result is the extremely high rate of citations to Justice Scalia’s opinions.” According to a recent analysis by Bloomberg Law, no justice has been invoked by name more often during Supreme Court arguments over the last 10 years – and no one else is even close. Again, the trend is bipartisan. As Adam Feldman recently found in a study of Supreme Court briefs, “Scalia is cited across party types and across administrations.”

What was Scalia’s secret weapon? Yes, he was brilliant and, yes, he was charming. But even more he was an unrivaled communicator. Many have tried to emulate him; none has succeeded. His opinions are still the punchiest, his speeches the wittiest. Even his books are good: his 1998 tome A Matter of Interpretation is the single most lucid defense of textualism and originalism that has ever been published.

It is true that textualism and originalism are not as popular in the legal academy. Tenure makes us a stubborn lot. But even we are consumed with Scalia. I published a study in the University of Chicago Law Review not too long ago that looked at how often each justice’s opinions appeared in constitutional law textbooks. Unsurprisingly, Scalia was at or near the top of every metric – even though his opinions were often not the controlling ones. He is even more dominant in our research: I ran the name of every Supreme Court justice through the Westlaw database of legal scholarship and no one appears in the titles of our articles more often than Scalia. Again, it isn’t even close: Scalia beats his closest rival, Justice Clarence Thomas, nearly three-to-two; he beats Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. three-to-one.

Of course, Scalia was not perfect and he of all people would not want his legacy degraded with hagiography; he didn’t suffer fools and wouldn’t want anyone else to suffer them either.

For example, it is fair to say that there is a growing realization that textualism and originalism are more complicated than Scalia let on. These complications have led to divisions among his adherents that critics use to cast textualists and originalists as unprincipled, inconsistent, or incoherent. These charges are mostly unfair – divisions are inevitable as an intellectual movement matures – but Scalia was largely disengaged from many of these complications.

Moreover, Justice Scalia’s tongue could bite and some think he contributed to the coarsening of our national discourse. He may have also been the first “celebrity” justice – he was the subject of both a play and an opera while he was still alive – and some thought his celebrity fostered tribalism. But these concerns seem quaint in the age of Trump, and it would be fantastical to draw a causative line from Scalia to Trump. Nonetheless, there is little doubt that the same qualities that made him so effective also rubbed many – including his less colorful colleagues – the wrong way.

Still, my prediction is that Scalia’s influence will only continue to grow. The reason is one more of his secret weapons: he helped create an entire organization dedicated to furthering his ideas. This organization is called the Federalist Society and it is now tens of thousands of members strong. It has chapters in nearly every law school and nearly every city. The state and federal judiciaries are filled with its members. True, organizations can drift over time, but this one shows no signs of it.

No other justice has ever left behind an entire organization dedicated to his or her ideas. But no other justice has ever been like Scalia.

Recommended Citation:

Brian Fitzpatrick,

Justice Scalia ten years later,

SCOTUSblog (Feb. 13, 2026, 10:00 AM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2026/02/justice-scalia-ten-years-later/